The electric vehicle supply chain is setting up shop in Brandenburg, despite local water resource concerns

Some in the region have argued that further industrial development poses risks to the freshwater system that also supplies Berlin, but they haven’t been able to put the breaks on big new investments into the battery-driven future.

Michael Grubb

Berlin 21.06.22

In August 2021, Elon Musk, the founder of the electric car manufacturer Tesla and often world’s richest man, stood in front of a group of reporters while visiting the construction site of the company’s latest factory outside of Berlin. He was accompanied by Armin Laschet, who at the time was the leader of the conservative Christian Democrat party and in the midst of a campaign to succeed Angela Merkel as Chancellor. Few politicians in Germany’s national spotlight at the time could reasonably pass up the opportunity to be pictured next to the enigmatic billionaire who had graced the country’s beleaguered East with such an enormous investment.

One of the reporters gave voice to the most prominent line of criticism that the undertaking has faced. “Mr. Musk, critics say that Tesla is stealing water from the region,” she said. Local activists have argued vehemently since the inception of the project that the company’s Gigafactory would impose an unsustainable strain on local water resources.

“No that’s completely wrong. There’s like water everywhere here,” Musk responded categorically. “Look around - does this seem like a desert to you?” The performative, guttural laughter that followed precluded any possibility of further engagement on the topic.

Tesla’s battery factory, still under construction, adjcent to it’s manufacturing plant in Grünheide, Brandenburg.

Photo: Michael Grubb 2022

It was a bit of theater featuring powerful men in suits, their foreheads glistening under the late summer sun, the raw cement shell of the unfinished factory serving as backdrop. It laid bare the constellation of risks and opportunities recent economic developments in the region pose, and the asymmetrical approach involved in weighing economic opportunity against environmental risk.

Tesla’s investment has drawn in other major projects – the area is now set to become Europe’s most significant center of electric vehicle production, bringing needed investment and jobs to this part of former East Germany. However, these developments pose risks to the region’s freshwater system, itself vulnerable to chemical contamination and strained by the effects of climate change.

Brandenburg’s bright economic future

“I believe that East Germany is in a very good phase of development,” Dietmar Woidke, Prime Minister of the State of Brandenburg told German Public Radio on the day that the Tesla Gigafactory officially opened in March 2022. “After 30 years, it’s about time I would say.”

Since reunification in 1990, the five states that comprised the former German Democratic Republic have lagged behind the rest of Germany by most economic measures. A significant labor productivity gap remains. High unemployment, lower annual income rates, and lower GDP per capita have all persisted.

So it is unsurprising that local politicians embraced Tesla’s bid to build its first European factory in Brandenburg, the German state that surrounds Berlin and borders Poland to the east. The process of approval for the company’s construction plans were expedited. The site itself had already once been slated for the construction of a BMW plant in the early 1990s, but which never materialized.

The company was allowed to begin construction even before local authorities had approved its plans – a strategy that greatly accelerated the project timeline, but which entailed Tesla taking on the risk that, in the event that the plans were in the end not approved, it would be obligated to return the site to its original state at the company’s own expense.

The approach taken towards Tesla has been hailed as a model for the future by local officials. The company went from making public its intentions, to having new cars coming off its assembly lines in under three years. It is difficult to overstate just how incredibly fast this undertaking came to fruition in Germany, a nation famous for its cumbersome bureaucracy and deliberative decision-making processes.

In the course of those three years, a string of new, large-scale investments revolving around the supply chain for electric vehicle production have followed Tesla to Brandenburg. The Canadian-German mining company RockTech is planning to build the largest lithium refinery in Europe in Guben, some 60 kilometers from Tesla’s Gigafactory. The company has said that by 2024 it will be able to produce 24,000 tons of the essential ingredient for batteries annually, enough for 500,000 electric cars. Further to the south BASF, the German chemical giant, has built a factory in Schwarzheide to produce enough cathodes for 400,000 electric cars annually, and is also building a prototype facility for the recycling of lithium batteries.

All of these investments bring technology, know-how and jobs to the region, and have put Brandenburg at the center of electric vehicle production in Europe. “Brandenburg will be one of the first regions in Europe that contains almost the entire electric car supply chain,” Dirk Harbecke, CEO of RockTech told the Handlesblatt newspaper in a recent interview.

A vulnerable water system

These investments all require large and continuous supplies of fresh water. The Tesla founder’s observation was not entirely false – the area does not look like a desert. The German state of Brandenburg is cut through by rivers and dotted with natural lakes. It’s not the Sahara, but the seeming abundance of water resources is deceptive.

“This region is the driest region in Germany, so you have to ask yourself if it makes sense to develop industry in a region where water is so scarce,” says Anna Lena Kronsbein, a PhD researcher at the Leibnitz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries in Berlin. She and her colleagues have pointed out that while the landscape may be covered with many bodies of water, the volume of water that moves through the system and is available for use by citizens and industry alike, is quite low.

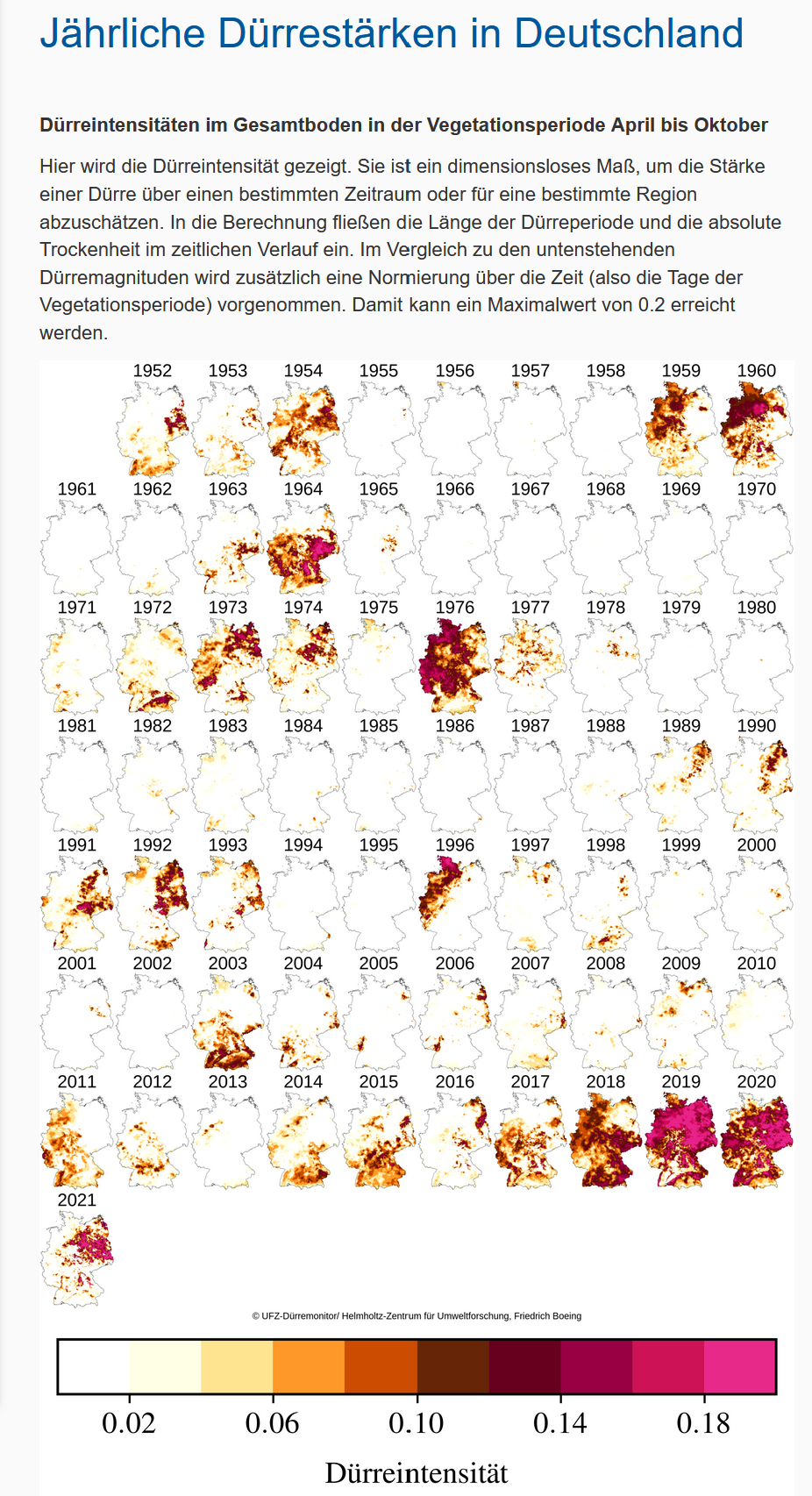

The figure shows drought intensity between April and October, from 1592-2021.

Source: Helmholz Zentrum für Umweltforschung

In Berlin and Brandenburg, surface water from lakes and rivers that infiltrates into the ground is utilized for drinking and industrial uses. The wastewater that is produced is treated and then fed back into the system – pumped into rivers and lakes where it is diluted. The process has functioned well in providing water to the region, but it is vulnerable. “It is a system that we have to take care of,” Kronsbein said.

The effects of climate change are already being felt – years of drought have meant lower levels of replenishment, and hotter temperatures in the summer months mean that more of the water that falls from the sky inevitably evaporates before it can enter the groundwater system.

“Right now we have way less rainfall, but also a decrease in groundwater levels,” Kornsbein said. “When the system is already stressed because of those two factors, which are manmade, and then we allow even more large-scale extraction, it makes the whole system more vulnerable.”

The other most significant risk to the system, according to Kronsbein, comes from potential contamination with certain types of persistent chemicals, which once in the system can be very difficult to remove.

Other, mor common pollutants such as sulfites which have been associated with coal mining operations that exist in other parts of the state, are currently mitigated through dilution. There is enough water currently moving through the system that their concentration can be kept at safe levels. However increasing levels of extraction may make this strategy untenable in the future.

“The system that we have now allows us a certain flexibility,” Kronsbein said. “If we don’t have enough water it means that we will be unable to solve problems that we may face in the future.”

Calculated risks

Both the potential for a large scale contamination of the groundwater system, and levels of extraction that exceed the rate of replenishment are the primary concerns voiced by groups of citizen activists who have campaigned to stop the construction of Tesla’s factory since it was announced in 2019.

“I as a citizen would not have thought that it would be possible to build an industrial factory in a ground water protection area,” Sabine Kutschick, of the Citizens Initiative Grünheide, told a group of activists gathered outside Tesla’s factory on a recent Saturday. She and her organization have led the campaign opposing the construction of the Gigafactory.

The heightened risk of groundwater contamination associated with Tesla’s factory comes from the fact that it is in part built atop a designated water protection area. According to Konsbein, the Leibnitz Institute researcher, these are areas that lie in close proximity to where groundwater and surface water interchange, meaning there is a high risk of chemical contaminants being able to enter the system there. Strict rules normally apply in these areas - it is, for example, illegal to park a car in a water protection area, as there would be a risk that substances such as motor oil or gasoline might leak from it and seep into the ground.

“This area supplies the region and Berlin, and we are risking the provision of water to the Capitol and the region through potential contamination. We already don’t have enough water.” Kutschick said

But in a region eager for large scale investment after 30 years of neglect, the political-economic considerations of the state have won out over the concerns of local activists. Political support for the project, at the state and federal level, has been broad based.

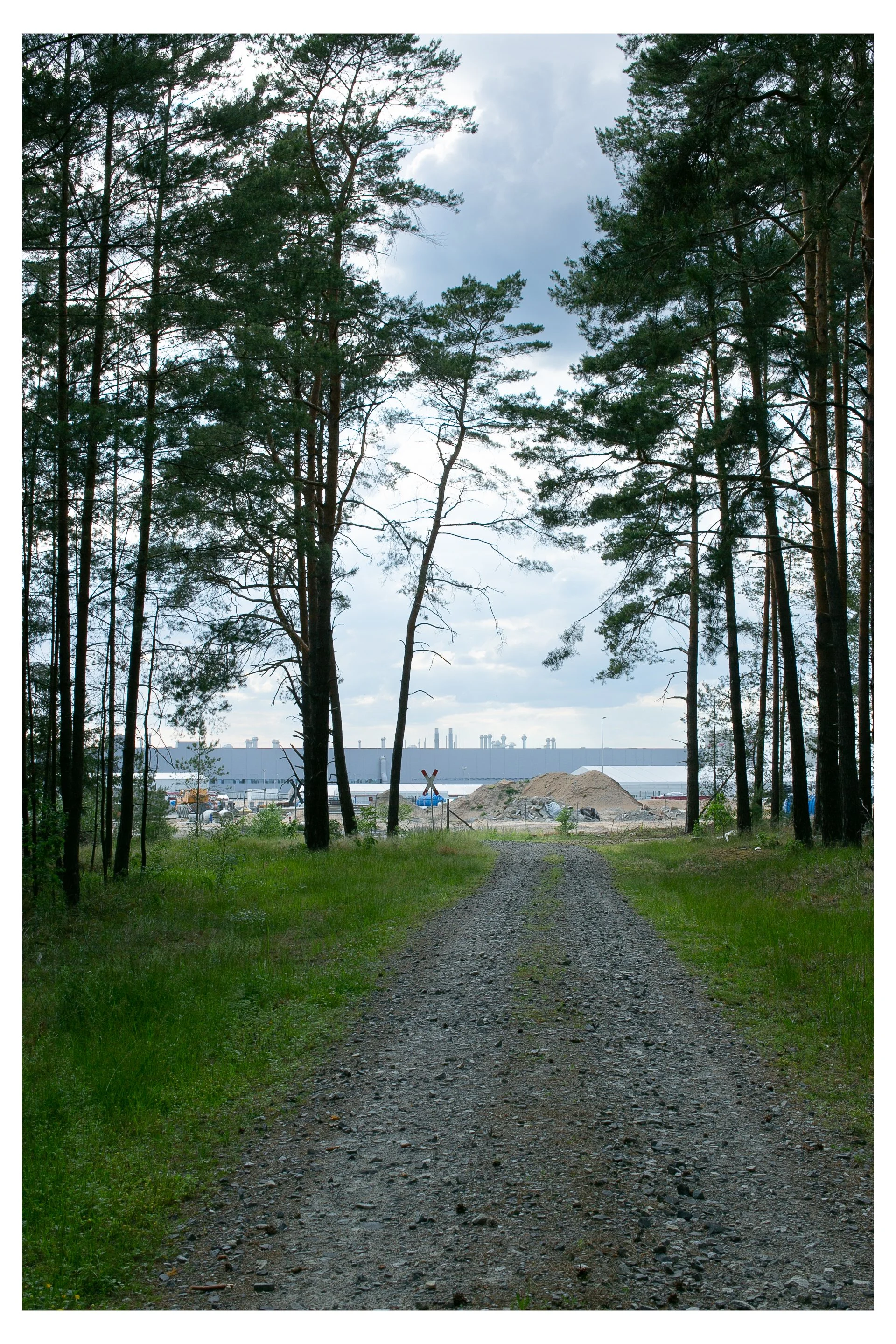

A forest service road leads to the construction site of Tesla’s Gigafactory in Grünheide, Brandenburg.

Photo: Michael Grubb 2022

Tesla submitted many thousands of pages of environmental reviews to the state government, which approved them, allowing the company to move forward on construction of its factory in the water protection area. The process was given a nod of approval even by Anton Hofreiter, head of the Green Party faction in the Bundestag. “The approval process has run smoothly and to the letter of the law,” he said after visiting the construction site in August 2021. “I think it is great that zero emission cars will be built here.”

Since then gleaming new electric cars have continued to roll out of the factory in Grünheide, but it remains an immense construction site. Kutschick, the local activist, led the group down underneath a highway overpass and along the fencing the abuts the cement shell of the soon to be battery factory. She pointed out the disorderly piles of construction material strewn about below swiveling cranes. The proximity to the site was accompanied by a cacophony of sounds – tanker trucks moving along the gravel roads, power tools in use, the sound of cars passing on the street behind.

She strained to raise her voice above it all. “Tesla is the blueprint for many projects that are coming in Germany. LNG terminals, wind energy projects; the citizens won’t see it coming, how quickly these things will simply be forced upon them.”

**This piece was produced as part of the coursework in the MA in Digital Journalism at the HMKW Berlin.